WHAT ROM-COMS TEACH US ABOUT LOVE

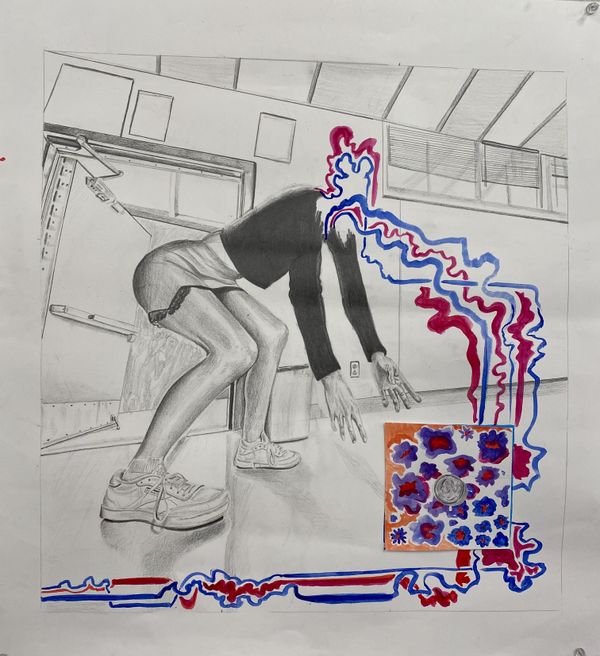

Art by Isabella Damberger-Sheldon

Lucia Rhiannon Harrison

9 December 2023

9 December 2023

I love rom-coms, or romantic comedies. I grew up on them, and yet they tend to present unrealistic ideals and conceptions about beauty and dating which we must unlearn to love fully and completely. It is no secret that rom-coms are presented to us from a capitalist perspective, with the goal of making money— but also in encouraging its audience to spend money. Our society today, arguably, doesn’t know how to love, flooded with greed and rampant individualism. Love is overcome by other priorities, like wealth.

To start, let’s examine love as defined by bell hooks. hooks says that love “is a combination of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust.” It is an act that must be performed continuously, and is both a noun and a verb. However, we commonly know love to be exclusively a noun. This definition of love directly contrasts myths of greed and individualism which we have grown into in the USA. In fact, we are presented with a myopic view of love; who gets to love and how to love. Film, media, and art reflects and reveals the interests and tensions of an era by what is projected on the screens.

Capitalism and depictions of love on the big screen have historically gone hand in hand. Think of the ways in which dating has been oriented around money-spending. Love is one of capitalism's most marketable franchises. Classic dates generally involve spending money of some kind, and heteronormative relationships contain set rules and standards for money-handling in these relationships. For example, the man should buy dinner. When dates that don’t involve spending money by either party are suggested, the internet is repulsed. Recently, there was backlash towards the idea of taking a walk as a date. Though not explicitly criticized for being a free activity, one must wonder why something so low-key which seems perfect for facilitating conversation is not a viable option for some. So much of dating is centered around spending money and the codes that go with it, including debates about women paying for themselves on dates. But this question is one which applies to straight relationships, while queer relationships are often spoken of in terms of straight relationships (like who is the man of the relationship) which assumes the dynamics of a straight relationship assigned to all relationships.

Society, in the United States, is largely structured around marriage. For those socialized as girls and women, marriage is seen as the end-all be-all of life. Though we have moved away—albeit slightly—from this narrative, the deep implications of this ideal prevail. Rom-coms often offer the fairy tale ending by way of a proposal or a marriage. Wedding films feed both the myth of the necessity of marriage and that this display of love must cost a ton, from the engagement ring (and the myth of diamonds) to the perfect wedding dress and the massive party, all of which are depicted in wedding films or “Cinderella stories.”

We are fed this idea largely through the media and products that we consume from childhood. From the womb, the child is gendered, even before becoming conscious. The child is instructed on how to be productive members of their gender, and scolded for existing outside of the lines. Take board games marketed towards girls. In the pink-flooded isles of toys, young girls will find games like LIFE which encourages young girls to find a boyfriend to ride with her in the car which travels across the board. Though a bit dated, examples from the late 90s of games marketed towards teenage girls reveal the socialization and encouragement of young girls towards dating and marriage. For example, in Girl Talk: Date Line, young girls are encouraged to match girl and boy cards to create dates.

Romantic comedies, and film in general, often mirror the values and anxieties of a moment in time. Through a look at these movies, we can start to understand the concepts being sold to us— particularly to the target audience of those socialized as women. Fairy tales and their remakes, particularly Disney movies, often feed this narrative to the point where a plot can feel empty without a love story ending. In The Happiness Illusion: how the media sold us a fairytale, Heather Brook breaks down two key elements of rom-com narrations: “an awakening (literal or metaphorical, but usually both)” and “an episode of magical (or somewhat magical) transformation.” Furthermore, it is important to note that romcoms also fetishize material objects, which is reminiscent of Robert Goldman’s concept of “commodity feminism” which, working together with neoliberalism, treats identity as maximizable through the right acquisitions, whereas neoliberalism tells you that your identity is “unlocked” through what you purchase.

Legally Blonde (2001) features Elle Woods who—to win her boyfriend back—attends Harvard Law school, endures a challenging time, eventually succeeds, “revealing” her intelligence in a high-profile caseand moving on from her boyfriend,finding love in Emmett, her law professor’s junior partner who by the end of the film (warning spoiler!) plans to propose. The film both presents the importance of believing in yourself and female empowerment, while also underlining “the importance and pleasures of feminine consumer culture.”

Evoking the “dumb blonde” stereotype, the film profited from the blonde look, encouraging it as an empowering choice surrounding the marketing of the film. However, in Legally Blonde, Elle faces no problems regarding economics or class, and her search for work is entirely self-motivated. Elle finds work and self-empowerment while also landing herself a boyfriend and possibly a fiancé. Elle’s big win is related to her knowledge of traditionally feminine practice, and thus opens the value (as seen from the male perspective) of understanding feminine consumer culture and to find value through your own personal style and beauty choices. As pointed out by the Los Angeles Times, as noted by Radner, “Clinique, Prada and OPI Nail Products are all prominently featured within the first five minutes of the film and Cosmopolitan Magazine is written into the script.” This product placement highlights the importance of consumerism in the film, as well as demonstrating how interconnected Elle’s identity is to consume, calling back Goldman’s “commodity feminism” once again. Also, notably, the film ends with a looming proposal from Emmett, never escaping far from the marriage-as-a-fairytale ending motif.

There is nothing wrong with love— love stories and romantic love— yet all the shapeshifting that romantic love undergoes in the media fosters a disillusionment about love, and most of all romantic love. Paired with an ethos of greed and individualism, it’s no wonder that the idea of love seems to grow further out of our reach. But, drawing on bell hooks in All About Love: New Visions, “the foundation of [true] love is the assumption that we want to grow and expand, to become more fully ourselves. There is no change that does not bring with it a feeling of challenge and loss.” We feel disillusioned because we both do not have the language to talk about love, but also because we have been fed misleading messages about love that benefit structures of domination, like capitalism and the patriarchy. If we learn to speak and think about love differently, then perhaps new cultural representations will follow, allowing us to truly explore what it means to love.

“Boys-R-Us” in Delinquents and Debutantes by Sherrie A. Inness

“Rom Coms and fairy tale endings” in The Happiness Illusion: how the media sold us a fairytale, by Heather Brooks, 147

“Legally Blonde (2001) “A Pink Girl in a Brown World” in Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks, and Consumer Culture, by Hillary Radner, 63

(“Legally Blonde (2001) ‘A Pink Girl in a Brown World” in Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks, and Consumer Culture, by Hillary Radner, 78).

“Romance: Sweet Love” in All About Love: New Visions, by bell hooks, 181-182.

To start, let’s examine love as defined by bell hooks. hooks says that love “is a combination of care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust.” It is an act that must be performed continuously, and is both a noun and a verb. However, we commonly know love to be exclusively a noun. This definition of love directly contrasts myths of greed and individualism which we have grown into in the USA. In fact, we are presented with a myopic view of love; who gets to love and how to love. Film, media, and art reflects and reveals the interests and tensions of an era by what is projected on the screens.

Capitalism and depictions of love on the big screen have historically gone hand in hand. Think of the ways in which dating has been oriented around money-spending. Love is one of capitalism's most marketable franchises. Classic dates generally involve spending money of some kind, and heteronormative relationships contain set rules and standards for money-handling in these relationships. For example, the man should buy dinner. When dates that don’t involve spending money by either party are suggested, the internet is repulsed. Recently, there was backlash towards the idea of taking a walk as a date. Though not explicitly criticized for being a free activity, one must wonder why something so low-key which seems perfect for facilitating conversation is not a viable option for some. So much of dating is centered around spending money and the codes that go with it, including debates about women paying for themselves on dates. But this question is one which applies to straight relationships, while queer relationships are often spoken of in terms of straight relationships (like who is the man of the relationship) which assumes the dynamics of a straight relationship assigned to all relationships.

Society, in the United States, is largely structured around marriage. For those socialized as girls and women, marriage is seen as the end-all be-all of life. Though we have moved away—albeit slightly—from this narrative, the deep implications of this ideal prevail. Rom-coms often offer the fairy tale ending by way of a proposal or a marriage. Wedding films feed both the myth of the necessity of marriage and that this display of love must cost a ton, from the engagement ring (and the myth of diamonds) to the perfect wedding dress and the massive party, all of which are depicted in wedding films or “Cinderella stories.”

We are fed this idea largely through the media and products that we consume from childhood. From the womb, the child is gendered, even before becoming conscious. The child is instructed on how to be productive members of their gender, and scolded for existing outside of the lines. Take board games marketed towards girls. In the pink-flooded isles of toys, young girls will find games like LIFE which encourages young girls to find a boyfriend to ride with her in the car which travels across the board. Though a bit dated, examples from the late 90s of games marketed towards teenage girls reveal the socialization and encouragement of young girls towards dating and marriage. For example, in Girl Talk: Date Line, young girls are encouraged to match girl and boy cards to create dates.

Romantic comedies, and film in general, often mirror the values and anxieties of a moment in time. Through a look at these movies, we can start to understand the concepts being sold to us— particularly to the target audience of those socialized as women. Fairy tales and their remakes, particularly Disney movies, often feed this narrative to the point where a plot can feel empty without a love story ending. In The Happiness Illusion: how the media sold us a fairytale, Heather Brook breaks down two key elements of rom-com narrations: “an awakening (literal or metaphorical, but usually both)” and “an episode of magical (or somewhat magical) transformation.” Furthermore, it is important to note that romcoms also fetishize material objects, which is reminiscent of Robert Goldman’s concept of “commodity feminism” which, working together with neoliberalism, treats identity as maximizable through the right acquisitions, whereas neoliberalism tells you that your identity is “unlocked” through what you purchase.

Legally Blonde (2001) features Elle Woods who—to win her boyfriend back—attends Harvard Law school, endures a challenging time, eventually succeeds, “revealing” her intelligence in a high-profile caseand moving on from her boyfriend,finding love in Emmett, her law professor’s junior partner who by the end of the film (warning spoiler!) plans to propose. The film both presents the importance of believing in yourself and female empowerment, while also underlining “the importance and pleasures of feminine consumer culture.”

Evoking the “dumb blonde” stereotype, the film profited from the blonde look, encouraging it as an empowering choice surrounding the marketing of the film. However, in Legally Blonde, Elle faces no problems regarding economics or class, and her search for work is entirely self-motivated. Elle finds work and self-empowerment while also landing herself a boyfriend and possibly a fiancé. Elle’s big win is related to her knowledge of traditionally feminine practice, and thus opens the value (as seen from the male perspective) of understanding feminine consumer culture and to find value through your own personal style and beauty choices. As pointed out by the Los Angeles Times, as noted by Radner, “Clinique, Prada and OPI Nail Products are all prominently featured within the first five minutes of the film and Cosmopolitan Magazine is written into the script.” This product placement highlights the importance of consumerism in the film, as well as demonstrating how interconnected Elle’s identity is to consume, calling back Goldman’s “commodity feminism” once again. Also, notably, the film ends with a looming proposal from Emmett, never escaping far from the marriage-as-a-fairytale ending motif.

There is nothing wrong with love— love stories and romantic love— yet all the shapeshifting that romantic love undergoes in the media fosters a disillusionment about love, and most of all romantic love. Paired with an ethos of greed and individualism, it’s no wonder that the idea of love seems to grow further out of our reach. But, drawing on bell hooks in All About Love: New Visions, “the foundation of [true] love is the assumption that we want to grow and expand, to become more fully ourselves. There is no change that does not bring with it a feeling of challenge and loss.” We feel disillusioned because we both do not have the language to talk about love, but also because we have been fed misleading messages about love that benefit structures of domination, like capitalism and the patriarchy. If we learn to speak and think about love differently, then perhaps new cultural representations will follow, allowing us to truly explore what it means to love.

“Boys-R-Us” in Delinquents and Debutantes by Sherrie A. Inness

“Rom Coms and fairy tale endings” in The Happiness Illusion: how the media sold us a fairytale, by Heather Brooks, 147

“Legally Blonde (2001) “A Pink Girl in a Brown World” in Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks, and Consumer Culture, by Hillary Radner, 63

(“Legally Blonde (2001) ‘A Pink Girl in a Brown World” in Neo-Feminist Cinema: Girly Films, Chick Flicks, and Consumer Culture, by Hillary Radner, 78).

“Romance: Sweet Love” in All About Love: New Visions, by bell hooks, 181-182.