MY BEST FRIEND’S TATTOO

OF THE VITRUVIAN MAN

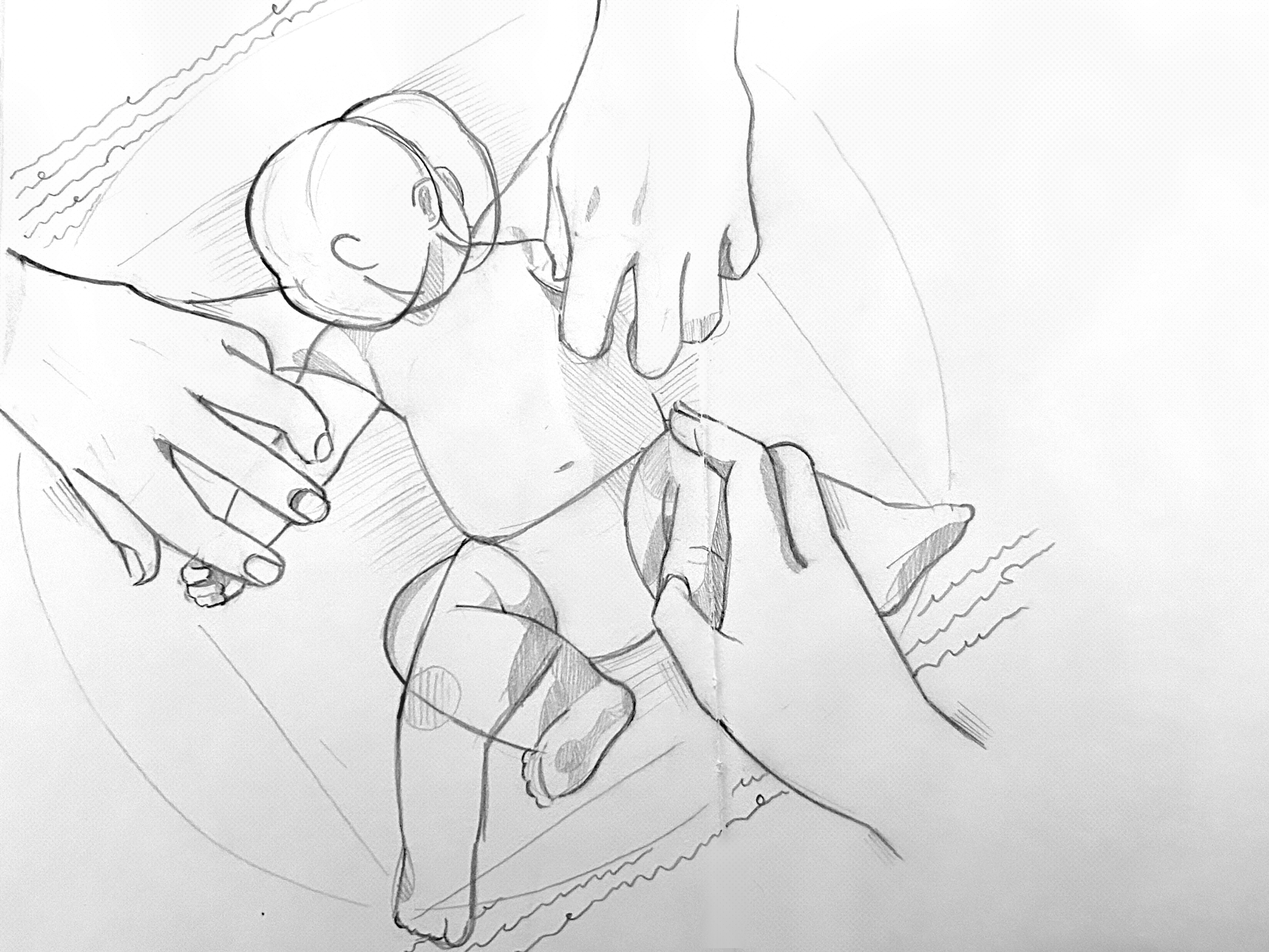

Graphic by Christina Lee

Graphic by Christina LeeRamitha Nagarajan

25 Februrary 2024

25 Februrary 2024

i. nascence/preservation

This is not about religion, but the preface is still necessary.

It first started at age four with Hindu religious comic books, which I’m pretty sure are a rite of passage for any Indian kid undergoing subtle religious indoctrination imposed by grandparents who buy them the entire Amar Chitra Katha (which literally translates to Immortal Picture Story) series at birth. And when I expressed even the slightest interest in a book with thousand-year old saints speaking English living in supersaturated green forests, I was already gripping at the concept of detachment, but fell at risk of adopting a romanticized version of it that would haunt me for years.

I remember one particular car ride as a third-grader after I had just learned about the Buddha in a conversation with my brother and the owner of a garden store who was selling us a fountain carved to look like Buddha’s head, with hair that I thought resembled Cocoa Puffs and a serene smile with closed eyes that felt almost patronizing, though I didn’t know that word existed at the time. On this car ride, it seemed easy: to sit under a tree, close my eyes, not think about anything, or not have anything with which to act on those thoughts. It sounds especially abnegative for a third-grader but my motives were megalomanic. I think I wanted the fame of Buddha, or Jesus, or of any God, and it makes me laugh now, but that sentiment of needing to be remembered and to make something larger than myself has manifested itself in countless ways deep into my adolescence.

I’ve obviously come to realize that renouncing it all may have just been easier when I was eight. The more years you gain, the more you realize that you have too much; that to renounce would mean to let go of everything, an everything that becomes bigger and bigger until something else you want to add to it makes your everything pale in comparison.

And at fifteen came my second realization about renouncement at my weekly Saturday evening Bhagavad Gita class, where sitting in a wooden gum-underbellied chair next to my then-best friend, I read Chapter 13, Verse 17:

“He is undivided, yet He exists as if divided among beings; He is to be known as the supporter of beings; He destroys them and creates them afresh.”

(I’m not one to presuppose the gender of God, although I’m pretty sure it isn’t a man.)

I still don’t know what this quote means on its own. But the anecdote that was taught to help me comes in waves every now and then. I was told that in every light bulb, the filament is the exact same, that in every wave the ocean exists, and the ocean exists in every wave. Which channeled the precocity I always knew existed within me, but at the time was the closest I’d gotten to absorbing renouncement.

ii. destruction/hollowing

My childhood best friend and I ended up parting ways, and I came to understand yet another tenet of renouncement, this time in my own life and not in some religious text that I probably didn’t have any need to read at an elementary level: the discovery that people are not replaceable, that your falling outs and losses are impersonal and a part of the collateral damage of falling more into yourself, both the shameful and good parts.

To be a mosaic of all the people you’ve ever loved, you have to be willing to shatter the glass guarding yourself and others and stain each other with your color. And when you can pick up the pieces, you’ll find you have come from something beautiful.

Sometimes these pieces aren’t people, they’re the tracks that got deleted off Spotify that have been dubbed “songs for women” in lowercase letters or “Traffic in the Sky” on Soundcloud, for which you’ll have to delete most of your camera roll to listen to. The ache of holding on. They’re the boys that you saw in Netflix original movies as an elementary schooler and A24 movies you watched and cried to during your self-important and slightly cumbersome middle schooler era. The bright red, slightly kitschy sweatshirt that says “J’aime” on it with a Facebook Like icon that you ditched for a mundane Pacsun Champion hoodie at fifteen because you’d decided hiding in bundles of cloth and high-waisted pants that enveloped your belly was safer than seeking yourself out again after years of self-loathing.

And all the dreams that mark a dawning. Dreams of future good taste, download after download of Erykah Badu’s “Bag Lady” and Rina Sawayama’s “Cherry” during the wormhole of quarantine. “When everyone was seventeen with no I.D…” The epiphany that A24 isn’t as indie as once thought and that Emma Seligman and Gerwig reign supreme, that I’d only unfortunately and tragically be attracted to boys that resembled Timothee Chalamet’s character in Lady Bird throughout high school. The first boy I’d really like (except for the dick in my 9th-grade math class who triggered some unspeakable empath-type tendencies), who would introduce me to the poet Charles Bukowksi, who would tell me to read “splash”, explaining that my writing resembled his, joking that the only brown rep I had, Rupi Kaur, was definitely jealous of my work. The printed ephemeral of Bukowksi’s “Face of a Political Candidate on a Street Billboard” I would buy a few years later at a bookstore, which I would eventually destroy in my suitcase coming to college but would pin up in my dorm room nevertheless. Ephemeral like the nature of the things I callous myself to cling to. The girl who became my best friend and has been ever since, and if reincarnation is real (which contradicts my previous deliberations on religion), will be in every lifetime. Epistemologically and non-denominationally-speaking, in every universe.

I still attend Bhagavad Gita classes, this time without the girl I once loved sitting next to me with whom I’d stifle laughs and now instead with girls I admittedly hate, who at my age, still continue (without even hiding it) to discredit our teachers for their perfect explications enshrouded in thick Indian accents.

My thoughts on religion are now subverted by agnosticism, but I’m proud of my progress; I reminisce on when I would ask tireless questions about Hinduism to my devout mother after she lit morning incense in the altar camouflaged in one of our kitchen cabinets. To me, the existence of a god of destruction made me feel ashamed to support a religion that endorsed demolition. I antagonized Hinduism until I realized the importance of destroying, ironically severing the negative connotation I’d imparted onto the word previously.

iii. flow/creation

As you grow older, the available space in the mosaic hanging above the altar of your body seems to grow crowded, the glass folding in to either shatter or melt into the color of your skin.

And the glass is fallible, you learn: you get rejected from the school you taped onto your vision board at fourteen, you realize Bukowski boy has funky philosophies bolstered by the books he buys from Moe’s (where you’ll frequent as a student at the college you actually end up at). You’ll realize you had no place in the business club you were an officer in throughout high school, that the world doesn’t need more investment bankers, that dissecting psyches is what you’ll do for the rest of your life in some form or the other. Through a failed short film, through a plethora of poems you write for your friends on an account under the name remirites, which comes from your namesake “remi”, the nickname your grandpa adorned you with as a baby. Through teaching your five-year-old neighbor with dyslexia how to read, wanting to jump and cry when he gets through his first level one book. When the girl you stupidly called your twin flame makes tears in your decade-long friendship when she taunts you with the words easy and immature as you break your shell and pray she doesn’t step on the pieces. The glass shatters and melts, then shatters and melts, and alchemizes into something you could never forge the shape of with your own mind. You remember when your friend explained Sawayama’s lyricism when she says “Inside I’m still the same me with no I.D.” while in her late 20s. No personal identity, still lost and somehow found because of it. And as you lose all control, you cling to words that you finally don’t have to chase the same way you did at eight and at fifteen, that you seem to be running at pace with: “everything [you’ve] ever let go of has claw marks on it”. You’ll eventually make this the description to a playlist solely composed of SZA’s Ctrl.

After moving out of the town you lived in for twelve years, you seem to drown in impermanence.

It kills you at first.

Ocean Vuong writes, “‘What were you before you met me? I think I was drowning.’" In your required philosophy class, you swallow lumps in your throat and feel warmth in your cheeks when asked to send compassion/forgiveness to your loved ones, and you think about your mom and dad who you had to hang up on during a video call by saying you had to study when in reality you couldn’t look at your mom’s newly gray hairs without sobbing. Your mother, who a week before you left for college, cried telling you it was okay that you liked girls, boys, and everyone in between, that she was sorry it took her five years to accept because her mind was stuck halfway across the globe with her parents. That your dad’s opinion on it did not matter, because in the words of another girl who preached for you to “be the cowboy” through your car’s dilapidated stereo, my love is mine. The short film that you spent a year planning and all your barista tips used trying to produce last summer rots on your Drive and you think about how to recompose it into something that still mirrors your eighteen. You desperately save letters from your 12th-grade English teacher who put you on Fleabag and from people-turned-strangers in a plastic Ziploc labeled “don’t lose; important”, reflecting your newfound appreciation for semicolons, and your Nintendo 3DS, with the very cunty Miis you and your brother made together years ago, in the bottom drawer of your dorm desk.

Then a saving grace.

‘"And what are you now? Water.’” In the same philosophy class, you learn about a religion named Daoism that you feel safe digging roots in, that speaks of life flowing like a river, being a natural unfolding of the being.

You find, with all the tears, an avalanche is made.

There are new friends who ricochet your ideas until they’ve shapeshifted. Friends who are full of shine before and during the party but tell you after about the rust that’s been growing under their skin while rewatching Kurtis Connor videos & eating 7/11 taquitos (they consequently become your best friends).

In your linguistics class, you learn about lambdas, which are convoluted and wholly unrelated to linguistics at first.

Because I still can’t explain them, here’s an example:

[λx.Sleep(x)](r)= Sleep(r)

If r stands for Ramitha, this would translate to “Ramitha sleeps”. But the r is interchangeable; the verb and the lambda still remain, but the people are allowed to slip away into sleep, into unconsciousness, and into nonexistence. Which sounds dramatic but is true; at the time you are learning about lambda calculus, you can only apply it to the language of detachment, x’s and y’s walking into and out of the doors you leave open to simmer the dynamism of your verbs, your movement, until they eventually cool to nouns, to static, to nothing at all.

You befriend an exchange student studying philosophy and English (who reminds you that you have an unfortunate penchant for philosophy students) who you become close to in a matter of weeks despite knowing she’ll have to leave in a matter of months. While watching a drunken game of pool, you tell her about a boy you’re worried might leave yet again, an x that feels heavier, for which you can’t see a y or z that might come after.

She reveals a tattoo on her right calf of leaves, and tells you that they are inspired by a Marcus Aurelius text she read years ago. “For all such things as these ‘are produced in the season of spring,’ as the poet says; then the wind casts them down; then the forest produces other leaves in their places. But a brief existence is common to all things, and yet thou avoidest and pursuest all things as if they would be eternal.”

And yet more ink on the skin, something your parents warned you was a permanent etching, that somehow reflects the complete opposite.

One evening in November, you’re broken-hearted for the first time atop the same wooden staircase next to the Greek Theatre where you established something real as Brockhampton played in the background. “See, I don't want nobody but you.”

You remember the long, dreadful A24 show you told him about once, and a laughable line that’s been stuck in your head since: “The Buddha is only the Buddha because he had something to renounce.”

Walking back to your dorm, your best friend, this time one that you only met six weeks ago but bonded with over queer-coded media and an Ikea bear named Djungelskog, sends you a picture of their first tattoo. It looks somewhat like da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a man with several arms extending out of his torso, a man of multitudes.

Once again, you are reminded of multitudes when you need it the most.

All your forms of healing that crash into you as the tears you’ve outpoured upon leaving home freeze in the winter cold and leave you utterly numb.

You remember a time when you were six, when your mom taught you basic color theory, when you were confused as to how every color in the rainbow combined, including those like cerulean and ochre, manifest themselves into the most mundane shade of white instead of multiplying their chromatic powers. Which, to a child that had just learned their multiplication tables, felt like how even multiplying the largest number you could think of by zero would result in zero. Which was futile and unfair to the eccentric colors and biggest numbers you doted at the time.

And currently futile and unfair to the most acute emotions you feel, because it all melts into nothing.

Unsobered and blue, you turn to a complementary color one midnight on the couch of your childhood home over winter break. As your parents sleep in the bedroom above, and the Buddha statue your mom bought from what feels like a lifetime ago maintains his upright cross-legged posture with a grin despite the showers outside, and as your brother screams at his friends on the phone, you romanticize the moment much like Lana del Rey does in her own account of men engrossed in the video games they play. Blood Orange streams through one ear and out the other, creates its own atmosphere, its own rings around the globe of your brain. With no inertia to bound and bridle you, you scraggily write in your notepad as any girl your age would, hoping for the words to not evade you, for the moment to remain permanent, for your brother to shut up for a second, trust that the Buddha will stay put:

“you can exist in multitudes: this is beautiful. this is the key to detachment. you were once the owner of this item, the significant other of this person, lambda x, lambda y, etc., wtv. but now you are free to be the owner of something else, someone else’s significant other. you can experience anything and everything else. you can detach from one thing and then find another that you can hold with your whole heart, this is the whole point. so experiencing the world and detachment are inextricably tied, and are mutually entailed, meaning that this must be the whole point: to experience.”

Upon reading it the next morning, you cringe at your Bojack Horseman-coded pretense, pray that nobody will find it, only to submit it as a part of your editorial debut in your first ever magazine the next spring. And even if you don’t read it again, if only to spare you from yourself, you can’t shake the feeling that everything, all the religion, all the ink, the molding of your heart, the swimming, the drowning, has paved its way to this.

“you can die now.

you can die now as

people were meant to

die:

great,

victorious,

hearing the music,

being the music,

roaring,

roaring,

roaring.”

This is not about religion, but the preface is still necessary.

It first started at age four with Hindu religious comic books, which I’m pretty sure are a rite of passage for any Indian kid undergoing subtle religious indoctrination imposed by grandparents who buy them the entire Amar Chitra Katha (which literally translates to Immortal Picture Story) series at birth. And when I expressed even the slightest interest in a book with thousand-year old saints speaking English living in supersaturated green forests, I was already gripping at the concept of detachment, but fell at risk of adopting a romanticized version of it that would haunt me for years.

I remember one particular car ride as a third-grader after I had just learned about the Buddha in a conversation with my brother and the owner of a garden store who was selling us a fountain carved to look like Buddha’s head, with hair that I thought resembled Cocoa Puffs and a serene smile with closed eyes that felt almost patronizing, though I didn’t know that word existed at the time. On this car ride, it seemed easy: to sit under a tree, close my eyes, not think about anything, or not have anything with which to act on those thoughts. It sounds especially abnegative for a third-grader but my motives were megalomanic. I think I wanted the fame of Buddha, or Jesus, or of any God, and it makes me laugh now, but that sentiment of needing to be remembered and to make something larger than myself has manifested itself in countless ways deep into my adolescence.

I’ve obviously come to realize that renouncing it all may have just been easier when I was eight. The more years you gain, the more you realize that you have too much; that to renounce would mean to let go of everything, an everything that becomes bigger and bigger until something else you want to add to it makes your everything pale in comparison.

And at fifteen came my second realization about renouncement at my weekly Saturday evening Bhagavad Gita class, where sitting in a wooden gum-underbellied chair next to my then-best friend, I read Chapter 13, Verse 17:

“He is undivided, yet He exists as if divided among beings; He is to be known as the supporter of beings; He destroys them and creates them afresh.”

(I’m not one to presuppose the gender of God, although I’m pretty sure it isn’t a man.)

I still don’t know what this quote means on its own. But the anecdote that was taught to help me comes in waves every now and then. I was told that in every light bulb, the filament is the exact same, that in every wave the ocean exists, and the ocean exists in every wave. Which channeled the precocity I always knew existed within me, but at the time was the closest I’d gotten to absorbing renouncement.

ii. destruction/hollowing

My childhood best friend and I ended up parting ways, and I came to understand yet another tenet of renouncement, this time in my own life and not in some religious text that I probably didn’t have any need to read at an elementary level: the discovery that people are not replaceable, that your falling outs and losses are impersonal and a part of the collateral damage of falling more into yourself, both the shameful and good parts.

To be a mosaic of all the people you’ve ever loved, you have to be willing to shatter the glass guarding yourself and others and stain each other with your color. And when you can pick up the pieces, you’ll find you have come from something beautiful.

Sometimes these pieces aren’t people, they’re the tracks that got deleted off Spotify that have been dubbed “songs for women” in lowercase letters or “Traffic in the Sky” on Soundcloud, for which you’ll have to delete most of your camera roll to listen to. The ache of holding on. They’re the boys that you saw in Netflix original movies as an elementary schooler and A24 movies you watched and cried to during your self-important and slightly cumbersome middle schooler era. The bright red, slightly kitschy sweatshirt that says “J’aime” on it with a Facebook Like icon that you ditched for a mundane Pacsun Champion hoodie at fifteen because you’d decided hiding in bundles of cloth and high-waisted pants that enveloped your belly was safer than seeking yourself out again after years of self-loathing.

And all the dreams that mark a dawning. Dreams of future good taste, download after download of Erykah Badu’s “Bag Lady” and Rina Sawayama’s “Cherry” during the wormhole of quarantine. “When everyone was seventeen with no I.D…” The epiphany that A24 isn’t as indie as once thought and that Emma Seligman and Gerwig reign supreme, that I’d only unfortunately and tragically be attracted to boys that resembled Timothee Chalamet’s character in Lady Bird throughout high school. The first boy I’d really like (except for the dick in my 9th-grade math class who triggered some unspeakable empath-type tendencies), who would introduce me to the poet Charles Bukowksi, who would tell me to read “splash”, explaining that my writing resembled his, joking that the only brown rep I had, Rupi Kaur, was definitely jealous of my work. The printed ephemeral of Bukowksi’s “Face of a Political Candidate on a Street Billboard” I would buy a few years later at a bookstore, which I would eventually destroy in my suitcase coming to college but would pin up in my dorm room nevertheless. Ephemeral like the nature of the things I callous myself to cling to. The girl who became my best friend and has been ever since, and if reincarnation is real (which contradicts my previous deliberations on religion), will be in every lifetime. Epistemologically and non-denominationally-speaking, in every universe.

I still attend Bhagavad Gita classes, this time without the girl I once loved sitting next to me with whom I’d stifle laughs and now instead with girls I admittedly hate, who at my age, still continue (without even hiding it) to discredit our teachers for their perfect explications enshrouded in thick Indian accents.

My thoughts on religion are now subverted by agnosticism, but I’m proud of my progress; I reminisce on when I would ask tireless questions about Hinduism to my devout mother after she lit morning incense in the altar camouflaged in one of our kitchen cabinets. To me, the existence of a god of destruction made me feel ashamed to support a religion that endorsed demolition. I antagonized Hinduism until I realized the importance of destroying, ironically severing the negative connotation I’d imparted onto the word previously.

iii. flow/creation

As you grow older, the available space in the mosaic hanging above the altar of your body seems to grow crowded, the glass folding in to either shatter or melt into the color of your skin.

And the glass is fallible, you learn: you get rejected from the school you taped onto your vision board at fourteen, you realize Bukowski boy has funky philosophies bolstered by the books he buys from Moe’s (where you’ll frequent as a student at the college you actually end up at). You’ll realize you had no place in the business club you were an officer in throughout high school, that the world doesn’t need more investment bankers, that dissecting psyches is what you’ll do for the rest of your life in some form or the other. Through a failed short film, through a plethora of poems you write for your friends on an account under the name remirites, which comes from your namesake “remi”, the nickname your grandpa adorned you with as a baby. Through teaching your five-year-old neighbor with dyslexia how to read, wanting to jump and cry when he gets through his first level one book. When the girl you stupidly called your twin flame makes tears in your decade-long friendship when she taunts you with the words easy and immature as you break your shell and pray she doesn’t step on the pieces. The glass shatters and melts, then shatters and melts, and alchemizes into something you could never forge the shape of with your own mind. You remember when your friend explained Sawayama’s lyricism when she says “Inside I’m still the same me with no I.D.” while in her late 20s. No personal identity, still lost and somehow found because of it. And as you lose all control, you cling to words that you finally don’t have to chase the same way you did at eight and at fifteen, that you seem to be running at pace with: “everything [you’ve] ever let go of has claw marks on it”. You’ll eventually make this the description to a playlist solely composed of SZA’s Ctrl.

After moving out of the town you lived in for twelve years, you seem to drown in impermanence.

It kills you at first.

Ocean Vuong writes, “‘What were you before you met me? I think I was drowning.’" In your required philosophy class, you swallow lumps in your throat and feel warmth in your cheeks when asked to send compassion/forgiveness to your loved ones, and you think about your mom and dad who you had to hang up on during a video call by saying you had to study when in reality you couldn’t look at your mom’s newly gray hairs without sobbing. Your mother, who a week before you left for college, cried telling you it was okay that you liked girls, boys, and everyone in between, that she was sorry it took her five years to accept because her mind was stuck halfway across the globe with her parents. That your dad’s opinion on it did not matter, because in the words of another girl who preached for you to “be the cowboy” through your car’s dilapidated stereo, my love is mine. The short film that you spent a year planning and all your barista tips used trying to produce last summer rots on your Drive and you think about how to recompose it into something that still mirrors your eighteen. You desperately save letters from your 12th-grade English teacher who put you on Fleabag and from people-turned-strangers in a plastic Ziploc labeled “don’t lose; important”, reflecting your newfound appreciation for semicolons, and your Nintendo 3DS, with the very cunty Miis you and your brother made together years ago, in the bottom drawer of your dorm desk.

Then a saving grace.

‘"And what are you now? Water.’” In the same philosophy class, you learn about a religion named Daoism that you feel safe digging roots in, that speaks of life flowing like a river, being a natural unfolding of the being.

You find, with all the tears, an avalanche is made.

There are new friends who ricochet your ideas until they’ve shapeshifted. Friends who are full of shine before and during the party but tell you after about the rust that’s been growing under their skin while rewatching Kurtis Connor videos & eating 7/11 taquitos (they consequently become your best friends).

In your linguistics class, you learn about lambdas, which are convoluted and wholly unrelated to linguistics at first.

Because I still can’t explain them, here’s an example:

[λx.Sleep(x)](r)= Sleep(r)

If r stands for Ramitha, this would translate to “Ramitha sleeps”. But the r is interchangeable; the verb and the lambda still remain, but the people are allowed to slip away into sleep, into unconsciousness, and into nonexistence. Which sounds dramatic but is true; at the time you are learning about lambda calculus, you can only apply it to the language of detachment, x’s and y’s walking into and out of the doors you leave open to simmer the dynamism of your verbs, your movement, until they eventually cool to nouns, to static, to nothing at all.

You befriend an exchange student studying philosophy and English (who reminds you that you have an unfortunate penchant for philosophy students) who you become close to in a matter of weeks despite knowing she’ll have to leave in a matter of months. While watching a drunken game of pool, you tell her about a boy you’re worried might leave yet again, an x that feels heavier, for which you can’t see a y or z that might come after.

She reveals a tattoo on her right calf of leaves, and tells you that they are inspired by a Marcus Aurelius text she read years ago. “For all such things as these ‘are produced in the season of spring,’ as the poet says; then the wind casts them down; then the forest produces other leaves in their places. But a brief existence is common to all things, and yet thou avoidest and pursuest all things as if they would be eternal.”

And yet more ink on the skin, something your parents warned you was a permanent etching, that somehow reflects the complete opposite.

One evening in November, you’re broken-hearted for the first time atop the same wooden staircase next to the Greek Theatre where you established something real as Brockhampton played in the background. “See, I don't want nobody but you.”

You remember the long, dreadful A24 show you told him about once, and a laughable line that’s been stuck in your head since: “The Buddha is only the Buddha because he had something to renounce.”

Walking back to your dorm, your best friend, this time one that you only met six weeks ago but bonded with over queer-coded media and an Ikea bear named Djungelskog, sends you a picture of their first tattoo. It looks somewhat like da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a man with several arms extending out of his torso, a man of multitudes.

Once again, you are reminded of multitudes when you need it the most.

All your forms of healing that crash into you as the tears you’ve outpoured upon leaving home freeze in the winter cold and leave you utterly numb.

You remember a time when you were six, when your mom taught you basic color theory, when you were confused as to how every color in the rainbow combined, including those like cerulean and ochre, manifest themselves into the most mundane shade of white instead of multiplying their chromatic powers. Which, to a child that had just learned their multiplication tables, felt like how even multiplying the largest number you could think of by zero would result in zero. Which was futile and unfair to the eccentric colors and biggest numbers you doted at the time.

And currently futile and unfair to the most acute emotions you feel, because it all melts into nothing.

Unsobered and blue, you turn to a complementary color one midnight on the couch of your childhood home over winter break. As your parents sleep in the bedroom above, and the Buddha statue your mom bought from what feels like a lifetime ago maintains his upright cross-legged posture with a grin despite the showers outside, and as your brother screams at his friends on the phone, you romanticize the moment much like Lana del Rey does in her own account of men engrossed in the video games they play. Blood Orange streams through one ear and out the other, creates its own atmosphere, its own rings around the globe of your brain. With no inertia to bound and bridle you, you scraggily write in your notepad as any girl your age would, hoping for the words to not evade you, for the moment to remain permanent, for your brother to shut up for a second, trust that the Buddha will stay put:

“you can exist in multitudes: this is beautiful. this is the key to detachment. you were once the owner of this item, the significant other of this person, lambda x, lambda y, etc., wtv. but now you are free to be the owner of something else, someone else’s significant other. you can experience anything and everything else. you can detach from one thing and then find another that you can hold with your whole heart, this is the whole point. so experiencing the world and detachment are inextricably tied, and are mutually entailed, meaning that this must be the whole point: to experience.”

Upon reading it the next morning, you cringe at your Bojack Horseman-coded pretense, pray that nobody will find it, only to submit it as a part of your editorial debut in your first ever magazine the next spring. And even if you don’t read it again, if only to spare you from yourself, you can’t shake the feeling that everything, all the religion, all the ink, the molding of your heart, the swimming, the drowning, has paved its way to this.

“you can die now.

you can die now as

people were meant to

die:

great,

victorious,

hearing the music,

being the music,

roaring,

roaring,

roaring.”